|

The

Pal Family Christmas card for 1949 photographed on the set of Destination Moon.

(Courtesy Gail Morgan Hickman from his book The Films of George Pal, Barnes 1977.) |

“It never ceases to amaze how the ripples begun by this wonderful Hungarian genius [George Pal] continue to influence so many in the motion picture industry.”

—Arnold Leibovit, film director, producer, screenwriter

“[T]he visual effects in Pal’s [Destination Moon] were art. They are aesthetically stunning ...

they bear the imprint of gifted artists’ hands.... [T]he Luna rocket of Destination Moon still [has] the

capacity to astonish.”

—Justin Humphreys in “A Cinema of Miracles: Remembering

George Pal,” from the memorial program notes for the Academy of Motion Picture

Arts and Sciences’ George Pal: Discovering the Fantastic—A Centennial

Celebration, August 27, 2008

Enthusiasts.

“Destination Moon is a film with

considerable dignity and, in a quiet way, a genuine sense of wonder.”

—Peter Nicholls in The

Encyclopedia of Science Fiction edited by John Clute and Peter Nicholls

Naysayers.

“Trivial in plot ... viewed today Destination Moon is less

than impressive; the rocket journey is ploddingly consistent with the

scientific standards of 1950...” —John Baxter in Science Fiction in the Cinema

Summary. Persuaded that the “other side” may get to the moon

first and establish a military base to hold the world hostage, American

industry (as opposed to any government agency) elects to build a rocket that

will travel to the moon. In an evenly-paced, almost documentary fashion, we get

to know the four men manning the rocket and experience with them the sensations

of traveling in space and landing on the moon.

|

| (courtesy Wade Williams Distribution) |

Comments. The 1950 film Destination Moon ought not be misapprehended,

maligned, or devalued, for the simple fact is that with no Destination Moon,

few of the movies in this blog (and in the book of the same title from which this blog is derived; see cover on right), if any at all, would ever have come into

existence. I’m a firm believer in prime sources and fate through connections.

It worked this way: Before Destination Moon, there were

ridiculously few serious science fiction films worthy of the term. One would

need to go as far back as 1929’s Frau in Mond (The Woman in the Moon), 1931’s

Frankenstein, and 1936’s Things to Come to find any worthy antecedent (1930’s

funfest Just Imagine and the Flash Gordon and other fantasy serials wouldn’t count

as they simply danced to a different drummer).

|

| A classic, poignant Puppetoon - Copyright © Arnold Leibovit |

By 1949, Pal was anxious to get into feature films. After

much effort, he convinced independent Eagle-Lion pictures to co-finance a

two-picture deal based on ideas he happened to be obsessed with at the time—as

long as he paid half the costs. The first picture, The Great Rupert, about a

Puppetoon-like dancing squirrel and starring then popular comic Jimmy Durante,

flopped. But the second picture, Destination Moon, was a different story. The

journey of its production and release is discussed below, but first I want to

make clear how positively vital the film is. Here is the short version:

Eagle-Lion’s publicity department proved to be on top of its

game when it saw the promotional possibilities of a picture about a rocket to

the moon. They promoted the hell out of it in both general family magazines and

the then rising star science fiction digest magazines, emphasizing its

Technicolor and its cadre of class-A consultants. Destination Moon was

constantly in the limelight of the popular press, including Life magazine,

and soon its success seemed a forgone conclusion.

Eagle-Lion’s publicity department proved to be on top of its

game when it saw the promotional possibilities of a picture about a rocket to

the moon. They promoted the hell out of it in both general family magazines and

the then rising star science fiction digest magazines, emphasizing its

Technicolor and its cadre of class-A consultants. Destination Moon was

constantly in the limelight of the popular press, including Life magazine,

and soon its success seemed a forgone conclusion.Enter Robert L. Lippert, a producer of very inexpensive, very quickly made films designed to veer droves of the unwary into theaters. He noticed all this nationwide publicity for Destination Moon and remembered that (1) longtime producer-director Kurt Neumann had not-too-long before offered him a script about a trip to Mars, which was populated with dinosaurs, and that (2) Jack Rabin, who owned a special visual effects company, had brought him an idea about a trip to the moon. Though Lippert was not interested in either pitch at the time, he changed his tune and he decided he’d be an idiot not to take advantage of all this free promotion for Destination Moon. While Destination Moon had been in production for two years and was costing more than half a million dollars, Lippert was able to combine Neumann’s and Rabin’s ideas to create a similar film, Rocketship X-M, with $94,000 and a shooting schedule of 18 days. In fact he made it so fast, it arrived in theaters a full month before Destination Moon.

|

| Eagle-Lion Promotion at the top of its form! |

For his 1995 volume, They Fought in the Creature Features,

film scholar Tom Weaver interviewed Lloyd Bridges, one of the stars of

Rocketship X-M, who said, “With Rocketship X-M we did beat our competitor,

Destination Moon. And they paid a lot more for their production. We kind of

took

advantage of the publicity they were putting out—people weren’t quite sure whether they were seeing that picture or our picture.”

advantage of the publicity they were putting out—people weren’t quite sure whether they were seeing that picture or our picture.”

Both films were huge popular and financial successes. (Rocketship X-M is also covered in this blog ss a sequel to this post; the productions of Destination Moon and Rocketship X-M are inevitably linked, and my two articles are intended to be read in sequence.)

If Destination Moon had failed, George Pal’s career could

well have died on the vine and he may have never made When Worlds Collide and

The War of the Worlds (1953). If those two Paramount films had not succeeded, there

would never have been Forbidden Planet or This Island Earth.

Just a tad slow getting started (not counting 1951’s Abbott

and Costello Meets the Invisible Man) by 1953 Universal-International Pictures

finally gets into the act, and soon we are fortunate enough to be graced with

It Came from Outer Space and The Creature from the Black Lagoon. On and on,

studio after studio, production company after production company, year after

year, the science fiction boom of the 1950s and 60s was upon us—all kick

started by George Pal and his Destination Moon.

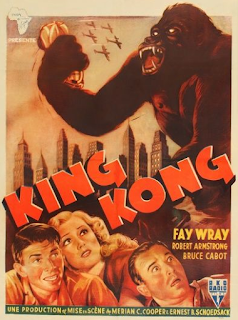

By 1952, as both audiences and executives were getting comfortable thinking “outside the box” and being happily diverted by overtly imaginative films (usually with special visual effects), then someone realized that it might be a good time to re-release RKO’s 1933 King Kong yet again (as pointed out by Bill Warren in his Keep Watching the Skies!). Bolstered by a heavy advertising campaign that included TV ads throughout the summer of 1952 (remember, this was when TV was still stalwartly making inroads into America’s living rooms), King Kong was a smash success, causing production companies (especially Warner Bros.) to realize that similar movies about giant monsters could also be successful. This ushered in countless giant creatures beginning with The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. The immense success of Beast inspired Warner Bros. to produce the giant-ants-on-the-loose picture—Them!—which in turn spawned a decade’s worth of giant insect movies.

By 1952, as both audiences and executives were getting comfortable thinking “outside the box” and being happily diverted by overtly imaginative films (usually with special visual effects), then someone realized that it might be a good time to re-release RKO’s 1933 King Kong yet again (as pointed out by Bill Warren in his Keep Watching the Skies!). Bolstered by a heavy advertising campaign that included TV ads throughout the summer of 1952 (remember, this was when TV was still stalwartly making inroads into America’s living rooms), King Kong was a smash success, causing production companies (especially Warner Bros.) to realize that similar movies about giant monsters could also be successful. This ushered in countless giant creatures beginning with The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. The immense success of Beast inspired Warner Bros. to produce the giant-ants-on-the-loose picture—Them!—which in turn spawned a decade’s worth of giant insect movies.

|

| 1952 re-release poster. |

The point that I’m making is that it is crystal clear that

the production and success of Destination Moon was the stone thrown into the

pond, initiating ripples upon ripples that have proven indelible and are

stronger today than ever. I feel that this is important and should not be

forgotten or taken for granted. I take issue with Warren who states in his Keep

Watching the Skies: “It is ... easy to overrate Destination Moon ... the film

is conventional, even a little dull” and also Gail Morgan Hickman, who writes

in his The Films of George Pal, “By today’s standards perhaps there is little

about Destination Moon to distinguish it.”

|

| (courtesy Wade Williams Distribution) |

“Destination Moon makes rather dull viewing nowadays.”

—John Brosnan in Movie Magic

.

.

“Destination Moon now seems tame.”

—John Stanley in Creature Features: The Science Fiction,

Fantasy and Horror Movie Guide

.

.

“[The] script seems colorless and wooden.”

—Phil Hardy in The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Science

Fiction

.

.

“Destination Moon has aged badly ... [it] seems old hat and

pedestrian to today’s viewers.”

—Barry Atkinson in Atomic Age Cinema

To my ear, these remarks seem no more than the half-baked

attempts of the writers to appease modern readers by appearing “relevant” and

“cutting-edge” and to gain their favor by casually dismissing anything that

smacks of being “old-fashioned.” Yes, some of these commentators—but not nearly

all—once having offered their aesthetic dismissal, perform an about face and

try to put the picture into historical perspective, for example, Atkinson goes

on to say, “But make no mistake about it, this picture, flaws and all, is a

very important step in the evolution of the serious, special effects-laden

science fiction motion picture that reached its peak with ... 2001: A Space

Odyssey.”

Why castigate and dismiss the film, making super clear why it is a failed film, only to turn right around to declare the film "an important step in the evolution."? It seems to me that a picture of Destination Moon’s

importance does not deserve the many negative judgments that are ascribed to it

so commonly today, judgments that can’t help but impact up-and-coming

audiences. And the respect that is accorded it, too often seems begrudging.

Some of this criticism stems from the fact that all creative

parties involved with Destination Moon wanted it to be as realistic and as

scientifically sound as possible. As a result, the film has a documentary

feel—which for some reason is anathema to many modern commentators who look

back on the film. The film was designed to make people think. Clearly it met

that goal far more than anybody could have imagined in 1950. How the picture

plays in relation to newer movies is utterly irrelevant. The newer movies might

not exist if it had not been for Destination Moon. Period.

One oft-repeated story that would seem to belie this

striving for realism is the fact that the Lunar surface in the movie is

crisscrossed with gaping cracks. Naturally this would imply that the surface

was once mud, which requires water, and the moon doesn’t have any water. Noted

artist and Hollywood matte painter Chesley Bonestell, who painted the large

backdrop that mimicked Lunar crags and mounts, was unhappy with the cracks,

which were designed by art director Ernst Fegté. “That was a mistake,” he

insisted to Hickman.

But Pal explained to Hickman, “Chesley was right, of course ... but we were shooting on a small soundstage because of our limited budget. We had to make the set look bigger. Chesley designed a beautiful backdrop, but it needed something to give it depth. That’s why we made the cracks. The cracks in the foreground were big and those in the distance were small, so it gave a real feeling of perspective. For some scenes we even used midgets in small spacesuits to add to the feeling of depth.” (Many readers will recall that the final airport scene in Casablanca also employed little people working around a cardboard cutout airplane in the foggy distance in order to give that dramatic scene perspective.)

|

| Note the improbable cracks (courtesy Wade Williams Distribution). |

But Pal explained to Hickman, “Chesley was right, of course ... but we were shooting on a small soundstage because of our limited budget. We had to make the set look bigger. Chesley designed a beautiful backdrop, but it needed something to give it depth. That’s why we made the cracks. The cracks in the foreground were big and those in the distance were small, so it gave a real feeling of perspective. For some scenes we even used midgets in small spacesuits to add to the feeling of depth.” (Many readers will recall that the final airport scene in Casablanca also employed little people working around a cardboard cutout airplane in the foggy distance in order to give that dramatic scene perspective.)

Destination Moon was groundbreaking in countless ways. Thus,

I feel a further word should be shared to explain how the film came to be.

First off, a movie about a rocket to the moon was an idea whose time had come.

In the late 1940s the idea seems to have sprung into the minds of a number of

movie people at the same time. Some of the names (but not nearly all)

associated with the birth (but not necessarily the completion) of Destination

Moon are William Castle; Chesley Bonestell; Hermann Oberth, who had been the

technical consultant for 1929’s Frau in Mond (The Woman in the Moon); Irving

Block; Jack Rabin; Robert A. Heinlein; Willy Ley, Lou Schor; Alford van Ronkel;

Peter Rathvon; Robert L. Lippert; Kurt Neumann; and George Pal. Block has said

that his and Jack Rabin’s version never got made “because there was so much

haggling.” It appears that at first William Castle, Rabin and Block, Kurt

Neumann, and Robert Heinlein all independently tried to launch rocket-to-the-moon

films, and it’s possible that, during their first attempts to garner outside

interest, none were aware of the others. In the end, it was Heinlein, Van

Ronkel, and Pal who made Destination Moon, while at the same time Rabin, Block,

and Neumann made Rocketship X-M—both films beginning as more or less the same

idea.

|

From concept in Jim Barnes’ aircraft factory, through

building, to finally ready for takeoff (courtesy Wade Williams Distribution).

|

All that said, I’m fascinated by the similarities between Destination Moon and 1947’s The Beginning or the End with Brian Donlevy. The first is a docudrama about persuading American private industry to pool their resources to build a rocket to the moon before the “other side” can. The second and earlier film is a docudrama about persuading American private industry to pool their resources to build an atomic bomb before the Germans can. Yes, while the American industry angle is central to co-script writer’s Robert A. Heinlein’s novella “The Man Who Bought the Moon,” I’m pretty certain that the realities of the Manhattan Project, or some reflection of it as shown in the Donlevy movie, influenced the making of Destination Moon.

Once audiences were in theaters and anticipations high,

Destination Moon began with a fabulous title sequence, perhaps not as dramatic

as in some of Pal’s later movies, but perfectly appropriate. Against a starry

background we see in the center of the screen a large moon, a Chesley Bonestell

painting, accompanied by genius Leith Stevens’ eerie score, which easily set

the mood for the entire movie. In fact, according to Hickman, “Stevens ...

consulted with numerous scientists, including Wernher von Braun, to get an idea

of what space was like in order to create it musically.” Taking this a step

further, Cy Schneider tells us in his liner notes from the 1960 Destination

Moon soundtrack Omega label stereo album:

|

| Destination Moon soundtrack CD |

The opening titles scroll up the screen much as we are used

to from all the Star Wars films (which in itself was borrowed from the 1939

Buck Rogers serial). The final frames of the movie treat us with a declaration

that would have been new and bold and exciting for audiences of the day: “The

End ... of the Beginning.”

Of special note, this film includes a charming and

delightful cameo appearance by Walter Lantz’ Woody Woodpecker. Because the

whole idea of rockets and rocketry had not yet become household concepts in

1950, as George Pal explains in The Films of George Pal by Gail Morgan Hickman,

“We wanted to explain what rocketry was in an amusing way.” In the scene where

a roomful of potential corporate sponsors are gathered to hear Jim Barnes’

sales pitch about sending a rocket to the moon, he shows a colorful short Woody

Woodpecker cartoon that helps seal the deal.

The Woody Woodpecker scene from Destination Moon

(courtesy Wade Williams

Distribution) The only science fiction movies I can think of that could be

considered of equal importance in terms of influence are Stanley Kubrick’s2001: A Space Odyssey and George Lucas’ Star Wars. Destination Moon has been

part of The Wade Williams Films Collection for many years. In 2000, Wade

Williams, Image Entertainment, and Corinth Films released a wonderful DVD with

great color that is still widely available.

July 1950. Eagle-Lion Classics Inc., George Pal Productions,

Inc. Technicolor. 1.37:1. 92m. Production Cost: $586,000. USA Gross:

$5,000,000.

CREDITS: Director Irving Pichel. Producer George Pal.

Screenplay James O’Hanlon, Robert A. Heinlein, Rip Van Ronkel; Inspired by Rocketship

Galileo by Robert A. Heinlein. Score Leith Stevens. Orchestration David Torbet.

Director of Photography Lionel Lindon. Production Designer Ernst Fegté. Editor

Duke Goldstone. Production Supervisor Martin Eisenberg. Technical Advisor of

Astronomical Art Chesley Bonestell. Sound William Lynch. Special Effects Lee

Zavitz. Cartoon Sequences Walter Lantz. Technicolor Color Consultant Robert

Brower. Technical Advisor Robert A. Heinlein.

CAST: Jim Barnes John Archer. Dr. Charles Cargraves Warner

Anderson. General Thayer Tom Powers. Joe Sweeney Dick Wesson. Emily Cargraves

Erin O’Brien-Moore.

Formal Notice: All images, quotations, and video/audio clips

used in this blog and in its individual posts are used either with permissions

from the copyright holders or through exercise of the doctrine of Fair Use as

described in U.S. copyright law, or are in the public domain. If any true

copyright holder (whether person[s] or organization) wishes an image or

quotation or clip to be removed from this blog and/or its individual posts,

please send a note with a clear request and explanation to

eely84232@mypacks.net and your request will be gladly complied with as quickly

as practical.

https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/mars-in-the-movies/

https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/mars-in-the-movies/

No comments:

Post a Comment

I invite anyone who likes my blog to comment. God bless!